Should eggs be washed and refrigerated?

Share

To wash or not to wash? That's the egg question.

Whether 'tis fresher at room temperature to preserve,

The cuticle around the shell, yolk and albumen,

Or to take soapy water against the forces of rancidity,

And by refrigeration end them! To rot - to spoil, no more.

- from my forthcoming play Omelette

-with apologies to Frans Hals and his work Young Man with a Skull

(Shakespeare, on the other hand, I think would be totally cool with parody)

I jest, of course. But seriously folks, there is quite a lively debate among both farmers and consumers in small farming circles about how fresh eggs are best handled. It's a two pronged question: first, should eggs be washed? and second, should they be refrigerated afterwards?

What is a fresh egg?

It's important to go into this with some definition of success. I propose that the goal is to keep eggs fresher, longer. In the studies that I looked at, the main aspects of freshness were albumen height, bacterial count (esp. Salmonella), and overall egg weight.

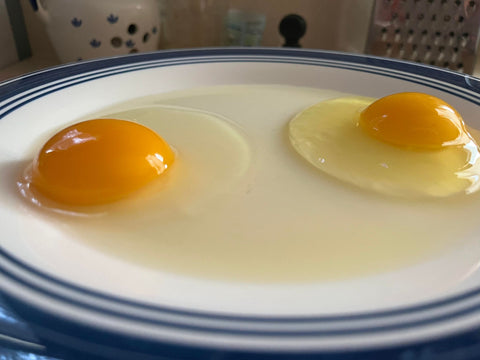

Albumen Height

The albumen is another name for the egg white. When you crack a fresh egg, the white spreads out much less than the white from an older egg. The more it spreads, the thinner it is, so albumen height becomes a handy way to measure how well an egg is ageing. The older the egg, the more thin and watery the white.

Fresh egg on the right (one day old), old but still edible egg on the left (14 weeks old, washed and refrigerated)

Bacterial Count

Some studies were more focused on the potential for salmonella from eggs. Salmonella can be on the outside or inside of the egg, or both.[1] Salmonella on the outside can be washed off but there is no way to remove salmonella on the inside. Since egg shells are porous, there it is also possible for bacteria on the outside of the egg to migrate inside through the shell. Often these are bacteria are not present in high enough numbers to cause anyone to get sick but whether they multiply or not depends on the conditions the eggs are kept in.

The other issue with salmonella is that it doesn't always go hand in hand with visible (or smell-able) spoilage. An egg can be affected enough to get you sick but still appear and smell perfectly fresh. There are plenty of other bacteria that like to multiply in eggs but most of them cause enough obvious spoilage that you wouldn't dare eat it!

Egg Weight

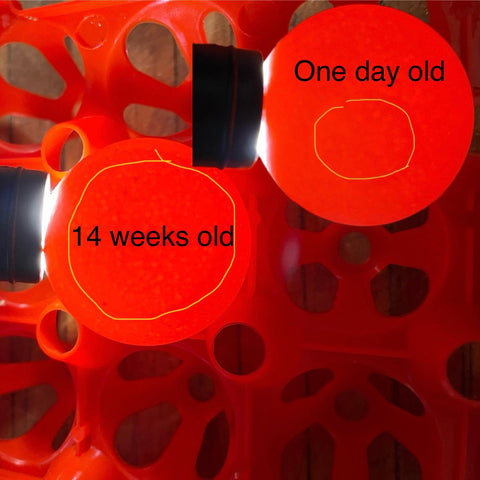

Eggs are porous because oxygen and moisture exchange through the shell is required for a chick embryo to develop. So even when not being incubated, eggs start to slowly dehydrate through the pores in the shell.[2] All but the absolute freshest eggs (less than a day old) have a small air pocket under the shell. This air pocket gets bigger as the egg ages. A process called candling (shining a bright light into the egg), allows us to see the size of this air pocket. This can also be tracked by regular weighing of the egg, since as it looses moisture it gets lighter.

Can you tell the difference in air sac size? Look for a faint circle near the center. The fresher egg is on the right, the older egg on the left

Washing

The world is somewhat divided on the subject of egg washing. The United States, Japan, New Zealand and Australia all wash eggs, while pretty much everyone else do not.[3] If you've ever collected fresh eggs, you can probably understand the urge to wash them. While eggs are often quite clean, they can also be covered, to varying degrees, in chicken poop. A chicken's vent (fancy name for butthole) is multipurpose, both eggs and poop come out of it. It's no wonder that sometimes they mix.

If you've ever bought eggs outside the countries of the washing club, you may have seen that these eggs sometimes have little bits of poop stuck to them. They were also likely not refrigerated. Egg washing and egg refrigeration go hand in hand. The reason for not washing eggs is a coating on the egg shell known as the "bloom" or "cuticle".[4] The cuticle allows air and moisture to be exchanged through the shell but not bacteria. Washing removes bacteria from the shell but can damage the cuticle, leaving it open to invasion from new bacteria. Unwashed eggs may still have bacteria on the shell but it cannot get inside the egg.

Refrigeration and Freshness

Since you can reasonably expect to buy grocery store eggs, whether washed or unwashed, and not get sick, let's put the salmonella question aside and instead address freshness. I'm not sure where the rumor got started but I occasionally hear from egg customers that they think eggs keep better if unwashed at room temperature. This is simply not true. Washed or not, eggs keep better in the fridge. In the UK, for example, unwashed eggs are sold at room temperature in the supermarket but are recommended to be refrigerated once brought home.[5]

I found a Brazilian study that demonstrated this quite well. The researchers kept eggs for a 9 week period, half refrigerated, half at room temperature and cracked open sample eggs daily to test for freshness. However, "During 9 week storage, only refrigerated eggs could be evaluated until the end of the experiment. The eggs stored at room temperature were withdrawn from the experiment after the 4th week, because as soon as eggs were opened, they were visibly rotten, with strong odor and flat surface due to the liquid albumen."

In countries where eggs are unrefrigerated, the use by dates are typically 21-28 days from the packing date, while in the US it is 45 days.[6] The Brazilian study looked at several indicators of freshness over the storage period and there was a much sharper worsening in all of them for the room temperature eggs.

I think where the confusion set in is that once refrigerated, eggs must continue to be refrigerated until cooking. Cold eggs that are allowed to warm up develop condensation which, especially on washed eggs, allows bacteria to move through the pores of the egg to contaminate the interior.[7] So, if refrigeration is inconsistent, it is better not to refrigerate at all. In fact, this is an excellent argument for not refrigerating eggs in many countries where the "cold chain" (keeping food cool from processing to consumer) may be inconsistent.

Maintaining a cold chain for eggs does consumes more energy, since refrigeration is required at every stage of storage and transportation. However, in the US we routinely transport eggs quite a long distance from production to retail stores. Refrigeration allows us to do this with minimal spoilage and minimal salmonella risk. In places that do not refrigerate, you will also often find more local production and thus shorter supply chains.

Food Miles

Just three states (Iowa, Ohio and Indiana) are responsible for a third of total US egg production.[8] And it's not because everyone in these states are consuming all those eggs, they are being shipped around the country. Surely, though, we could save energy by localizing egg production and de-refrigerating the egg supply chain?

Not so fast! Egg production is concentrated in the Midwest in large part because that's where we grow the most grain. Chickens need a lot of grain! Even in pastured systems, the grass and bugs provide a nutrition boost and enrichment activity, rather than sustenance (Read Why there's no such thing as a grass-fed chicken). So raising chickens near where we raise their food saves on the transportation of grain. Since hatcheries are also concentrated in the Midwest, it saves on the transportation of the chickens themselves as well.

California, for example, does not pull its weight at all in terms of egg production. It is the most populous state in the union but barely ranks in the top ten for eggs.[9] Since we know that moving only egg production there would incur the increased costs and energy usage of grain and chick transportation, let's move some hatcheries and grain production over there too. Except...have you ever tried to buy farmland in California? You might be able to guess that California farmland is really expensive (only in New Jersey does it cost more per acre!) [10] California is uniquely suited to certain fruit and nut tree crops and year round vegetable production. Are we going to sacrifice some of that production for the sake of local California eggs?

Those local eggs are still going to be more expensive than shipped-in Midwest eggs because mortgage payments, inputs and labor are all more expensive for producers. Not to mention most grains will not be happy with droughty California summers, so there will be higher rates of crop failure and more issues with water rights. It is neither energy efficient nor ecologically sensible to grow crops in an environment that they're not suited for.

Once we know all that, shipping eggs in refrigerated trucks is actually a more efficient way to go about large scale egg production! Production costs are cheaper and thus it is cheaper for the consumer.

Cheap or Good? (Both?)

That is not to say that commercial egg production is a glowing example of environmental sustainability and animal welfare. Nitrogen runoff from chicken manure is a huge issue for waterways near any type of poultry production. Animal welfare issues come into play too. But the reason for these issues isn't the size of the operation.

I speak from the perspective of a small scale Vermont egg producer. I raise laying hens in a way that the big producers don't. Not only do they eat organic grain year round but from April to October (the months without snow cover in Vermont) they are out on pasture eating grass and bugs and basking in the sunshine. The health boosts from this kind of living means they don't need constant low dose antibiotics to stay healthy and they don't need to have their beaks trimmed to stop them from picking each other's feathers out. The eggs they lay have bright yellow yolks and are on store shelves within a few days of being laid.

My laying hens hitting the pasture just as the grass starts to green up in Vermont (mid April!)

But the flip side is that there is no blueprint for scaling up this kind of operation. And with 250 hens I get only minor benefits from economies of scale. This is the main reason why my eggs are $6.25/dozen, while you can get eggs in the grocery store for half that or cheaper. The sustainable agriculture world has spent too much time tooting the horn of "small farms will save us". The focus has been on convincing the consumer to suffer $6-$8/dozen eggs, rather than bringing production costs down while maintaining high standards of sustainability and animal welfare.

Are those standards worth the price? I certainly think so! But I am also speaking from the privileged position of not having to worry much about my food budget. I have never gone hungry because I couldn't afford food. As a producer I am lucky to live in an area where there are plenty of people willing and able to pay a premium for organic, pasture-raised eggs.

If instead of guilt tripping the consumer into buying expensive food, we focused on scaling up more humane, environmentally friendly food production, we could have both good AND cheap food. But it will be a long process and I think everyone still deserves access to cheap, nutritious food like eggs while we figure out how to do that.

To wash or not to wash?

We seem to have taken a few detours on the way to our answer. I think the best answer is everyone's (least) favorite: if depends! It turns out context is important. If eggs are coming from nearby and/or don't have a reliable cold chain from producer to consumer, the best bet is probably no washing and no refrigeration. However, unwashed eggs SHOULD be washed by the consumer before use. In the United States most people are not used to this. State and local regulations also typically require egg washing by all but the smallest producers. This is why even as a small, local producer I do wash and refrigerate eggs.

Eggs that are being transported longer distances and spend more time reaching their final destination should definitely be washed and refrigerated. It also means that you can buy eggs less often even if you don't use them very regularly. Properly (that is, consistently) refrigerated eggs can last for months, while room temperature eggs are near the end of edibility after just three weeks. [12]

Thanks for sticking with me! If you're still interested in finding out more about this topic, peruse the references list. Mixed in with the dry academic studies are further reading on adjacent topics and some great Instagram reels on US egg production.

References

USDA Sources

https://www.fsis.usda.gov/food-safety/safe-food-handling-and-preparation/eggs/shell-eggs-farm-table

https://www.usda.gov/media/blog/2020/04/14/egg-stat-ic-about-eggs

https://ask.usda.gov/s/article/What-are-the-egg-grades

https://tellus.ars.usda.gov/stories/articles/how-we-store-our-eggs-and-why

https://tellus.ars.usda.gov/stories/articles/how-we-store-our-eggs-bonus-content

Published Studies

Egg quality assessment at different storage conditions, seasons and laying hen strains

https://www.scielo.br/j/cagro/a/DVnqtYBHjzQV6dwqgKBdPpq/?lang=en#

Effects of extended storage on egg quality factors

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0032579119447317?via%3Dihub

Effect of Egg Washing on the Cuticle Quality of Brown and White Table Eggs

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0362028X22115528?via%3Dihub (Interestingly, this study found that the cuticle was NOT damaged by washing. At least in this one particular Swedish egg washing factory)

From Sylvanaqua Farms via You Tube (updated June 2025)

Washing Eggs in the US

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G7nN6nuRpkw

European vs. US egg production

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UWrVN1zEAg4

Miscellaneous

https://www.organicvalley.coop/blog/why-does-us-refrigerate-eggs/

https://acretrader.com/resources/farmland-values/farmland-prices

1 comment

This was such a great take on egg practices and large scale agriculture in general. Plus, I got the satisfaction of learning I was right (to refrigerate unwashed eggs rather than leave them at room temperature) in an argument I had thirteen years ago! Ha. Still counts.